Egg Binding in Pet Birds

By Dr Andrew Vermeulen, BVSc, MANZCVS (Unusual Pets, Avian Health)

Egg binding, or dystocia, can be defined as an abnormal rate of passage through the oviduct and an obstruction of the caudal salpinx/cloaca respectively. The first point to note is the need for clarity from the client on the gender of their bird on arrival, as most owners are unaware due to absent or subtle sexual dimorphism in companion birds.

Presentation and history commonly given

Egg bound birds will commonly present with lethargy, depression, anorexia, an abnormal stance, paresis of pelvic limbs, in advanced cases paralysis or even fracture of pelvic limbs, coelomic cavity swelling, varying degrees of respiratory distress, and cloacal prolapse. Common causes of egg binding are malnutrition, lack of exercise, obesity, lack of UVB, myopathies, systemic disease, oversized eggs, or injury from previous dystocia.

An initial approach to ascertaining if an egg is present is through a thorough history taking, but with special focus on:

- Sexual behaviours

- Number of clutches or eggs laid

- Time since the last egg laid

- Time since straining first noticed OR start of any of the above-presenting signs.

Before a physical examination is started it is prudent to focus on the respiratory effort of the patient. As birds lack a diaphragm there will be a high risk of asphyxiation and collapse with prolonged handling. Flow by oxygen supplied by nursing staff is recommended. During an exam, gentle palpation of the coelomic window with the index finger will in most cases allow recognition of a calcified egg by pressing cranio-dorsally. However, in some cases, the egg may be present too far cranio-dorsally to palpate, and excess force can iatrogenically rupture a poorly calcified egg.

An initial imaging approach can be undertaken via a dorso-ventral radiograph, commonly referred to as a ‘Bird-in-box’ radiograph. This allows assessment of calcified egg presence and can give an understanding of more than one egg is present. Complications may include an egg that is external to the reproductive tract due to retroperistalsis or uterine tears.

An ultrasound is required for those which have eggs in the salpinx but not yet calcified also commonly known as soft-shelled eggs.

Physical examination

Before a physical examination is started, it is prudent to focus on the respiratory effort of the patient. As birds lack a diaphragm there will be a high risk of asphyxiation and collapse with prolonged handling, thus flow by oxygen supplied by nursing staff is recommended. During exam, gentle palpation of the coelomic window with the index finger will in most cases allow recognition of a calcified egg by pressing cranio-dorsally. However, in some cases, the egg may be present too far cranio-dorsally to palpate, and excess force can iatrogenically rupture a poorly calcified egg.

Initial diagnostics

Our recommendation for owners at this stage are to pursue further diagnostics which include serum biochemistry, complete blood count, positional radiography, and ultrasonography.

The diagnostics are staggered based on patient size, stability and relevant usefulness of information expected to be received from each test. Diagnostics are either forgone or postponed if the pet is not stable.

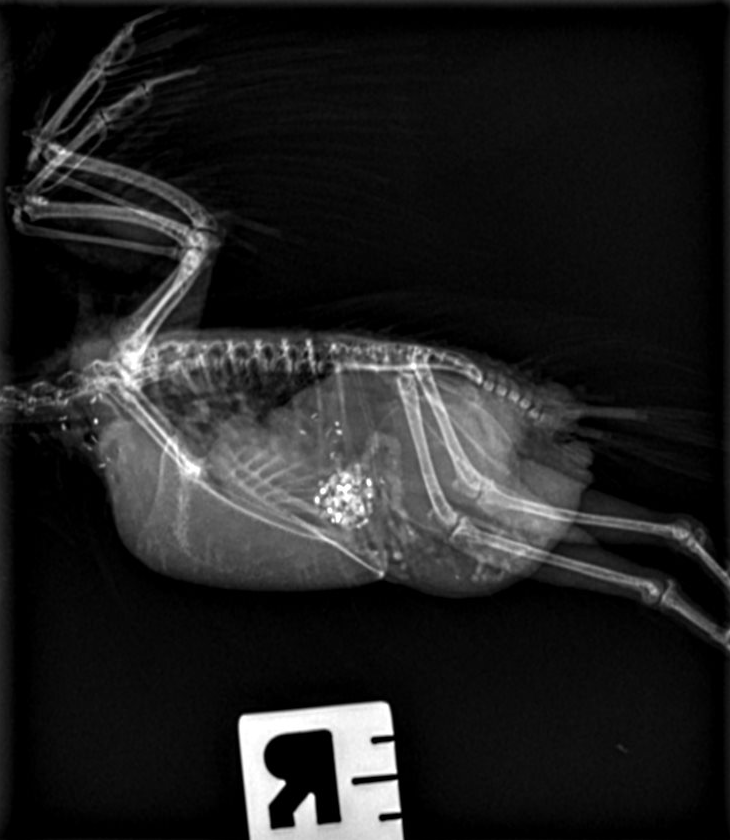

An initial non-invasive imaging approach can be undertaken via a dorso-ventral radiograph, or commonly referred to as a ‘Bird-in-box’ radiograph as seen in Figure 1. This allows assessment of calcified egg presence and can give an understanding if more than one egg is present. However, this does not allow the clinician to assess for complications such as an egg that is external to the reproductive tract due to retroperistalsis or uterine tears.

Figure 1 - Dorsoventral projection unrestrained radiograph showing a calcified egg in the caudal coelom.

If an egg is not clearly seen, but egg binding remains suspected due to coelomic distension with soft tissue/fluid opacity on radiography as in Figure 2, An ultrasound is then required to visualise the egg structure within the salpinx. This will appear as a bullseye effect, with a hyperechoic centre (yolk), hypoechoic outer ring (albumin) and thin hyperechoic circumferential margin (membrane) as seen in Figure 3. Viewing the egg structurally using this approach also aids in assessing if the egg has become degenerative.

Figure 2 - Positional radiographs showing coelomic distension with soft tissue/fluid opacity in the dorso-caudal coelom.

A common finding of positional radiography, serum biochemistry and complete blood count respectively will include hyperosteotic cortices and medulla of the long bones, hypercalcemia, varying degrees of metabolic abnormalities dependent on duration of binding, and stress leukogram.

Initial medical therapies and hospitalisation

Following this triage and diagnostics assessment, an initial treatment is recommended to be given up to 12 hours. A standard approach is as follows (with alteration dependent on biochemistry/ complete blood cell count findings):

- Incubator or warmed/humidified enclosure (30 degrees) with dimmed lighting or covered to allow semi darkness.

- Oxygen therapy (as needed)

- Butorphanol 2-4 mg/kg IM q1.5-4h

- Subcutaneous fluid therapy - 35-50ml/kg of Plasma-lyte

- Calcium gluconate 50-100mg/kg IM

- Small volume easily digestible energy source by gavage feeding i.e., Polyaid-Aid Plus (Vetafarm, Australia)

Anecdotal use of oxytocin has been described but the drug has not been added to the above triage list due to two main factors, the first being that it is not considered an avian hormone. There is currently no scientific evidence supporting therapeutic effectiveness of oxytocin, and the second factor to consider is that if the uterovaginal sphincter is not open then forceful contractions will cause pain, risk of uterine tearing and even death. Other safer hormonal therapies include Arginine Vasotocin, and Prostaglandin E2α but at this point these drugs are not available locally.

Assessment for referral

Following medical management, if no progress is seen and the egg is not passed, a case for referral is warranted unless you are comfortable to further treat these patients.

Manual manipulation and removal under anaesthetic

Removal of the egg is performed routinely under isoflurane anaesthesia. This allows control of respiration via intubation in birds over 100g or via adequate oxygen administration by mask, as well as removal of patient stress and smooth muscle contraction during egg manipulation. The cloaca is assessed at first by application and exploration using two lubricated cotton tips with sterile water-based lubricant. If the egg is not visible within the cloaca/vagina, then dorso-cranial digital compression is applied to the cranial aspect of the egg, and it is moved caudally to allow visualisation of the exteriorised vagina. Careful monitoring of patient respiratory rate is needed by nursing staff due to the compression on the caudal thoracic and abdominal air sacs. The opening of the uterovaginal sphincter is often visualised as a <1mm diameter white circular area due to the presence of eggshell. A small amount of dilation can be achieved by manual gentle stretching with instruments or cotton tip application.

Percloacal ovocentesis

Percloacal ovocentesis is employed at this time with an expected success rate of 80%. An 18-gauge, 1-inch (25 mm) needle, with 3ml leurlock syringe, is gently bored into the eggshell and the contents aspirated. The needle is not manipulated inside the egg or angled as this may cause iatrogenic puncture cranially. Once the egg is drained sufficiently, the needle is withdrawn, and firm digital pressure is applied on lateral aspects until collapse occurs. If this is not occurring easily, a second bore hole is created to allow a more focal point of weakness and then collapsing is reattempted.

Following collapse of the egg it is important to maintain dorso-cranial pressure of the eggshell so that visualisation of the uterovaginal sphincter is not lost. The eggshell is then gently exteriorised by either placement of a cotton tip in the egg lumen and a scooping motion applied, or by use of ring tip forceps to remove egg fragments. Gentle warm saline flushing of the cloaca to remove any debris can then be performed. The salpinx itself is not irrigated to avoid retropulsion of content.

In a small number of cases, the eggshell cannot be retrieved, or visualisation of the uretero-vaginal sphincter is lost. When this occurs, the eggshell may be left within the salpinx and the patient recovered from general anaesthetic. With continued supportive care for up to 24-36 hours, the majority of eggshell remnants are expected to pass unaided. Passage of remaining fragments is confirmed by repeated radiographs. If this does not occur, and the patient is stable, a repeat general anaesthetic to attempt removal of remaining fragments may be pursued.

In cases of a diseased uterus, observable uterine tearing, stricture with inability to pass eggshell, or severe adhesions of shell to the uterine lining, it is recommended to pursue salpingohysterectomy. This surgery carries significant risk especially if the bird is debilitated. After the uterus is removed there is still a need to manage ongoing risk of ectopic ovulation as the ovary cannot be safely surgically excised. Salpingotomy, or avian caesarean section, is also possible in select cases.

Post removal medical hormonal management

Following egg removal, it is strongly advised to place a Suprelorin 4.7mg (deslorelin acetate), a GNRH-receptor agonist, implant subcutaneously. This will prevent further recurrence of egg binding and allow time for discussion of husbandry factors that have led to this occurrence in the pet bird presented. Reports of duration of action include 10 weeks in Japanese quail, 5 weeks in pigeons, 6 weeks in mallard ducks, 6 months in chickens, 4-5 months in cockatiels, 9 months in budgerigars, and 10 months in sun conures.

Leuprolide acetate depot injection is a GNRH-receptor agonist alternative; however, this requires repeat dosing every 2-3 weeks and may not be financially suitable long term.

Conclusion

Egg laying can be a very challenging and frustrating disease process to manage. The risks of extracting an egg should be discussed thoroughly with owners but its urgency should be also highlighted. It is unlikely for a sick bird to pass an egg naturally if it does not do so after 12-24 hours of supportive care. It is imperative that the avian vet has an extensive discussion regarding husbandry and causal factors of egg laying in companion birds for long term prevention. The cage setup, daily routine, diet, and owner interactions with the bird should be altered if needed to reduce stimulation of chronic egg laying.

References

- Disorders of the reproductive system. (2015). In J. Samour (Ed.), Avian Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Rosen, L. B. (2012). Avian Reproductive Disorders. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 21(2), 124-131. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2012.02.013

- Rosen, L. B. (2012). Avian Reproductive Disorders. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 21(2), 124 - 131.

- Doneley, B. (2016). Disorders of the reproductive tract. In Avian Medicine and Surgery in Practice: Companion and Aviary Birds (pp. 317–332). CRC Press.

- Pituitary gland. (2014). In C. G. Scanes (Ed.), Sturkie's Avian Physiology (pp. 497–535). Elsevier Science.

- Tariq, A. Z., Carrasco, D. C., Jones, S. L., & Dutton, T. A. (2019). Percloacal Ovocentesis in the Treatment of Avian Egg Binding: Review of 20 Cases. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 33(3), 251–257.

- Scagnelli, A. M., & Tully, T. (2017). Reproductive disorders in parrots. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract., 20(2), 485–507.

- N, S. M., Guzman, D. S., Wils-Plotz, E. L., Riedl, N. E., Kass, P. H., & Hawkins, M. G. (2017). Evaluation of the effects of a 4.7-mg deslorelin acetate implant on egg laying in cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus). American Journal of Veterinary Research, 78(6), 745 - 751. doi:10.2460/ajvr.78.6.745

- Mitchell, M. A. (2005). Leuprolide acetate. Semin Avian Exotic Pet Med., 2005(14), 153-155.

Image resources

www.omlet.co.uk/guide/budgies/varieties_and_types/sexes/

www.shutterstock.com/g/Mauvries

www.flickr.com/photos/blomeruscalitz/2914881633

www.chekyang.com/musings/2008/09/04/bali-bird-park/

birdscoo.com/care/cockatiel/sexing-cockatiels

www.petplace.com/article/birds/general/choosing-a-lesser-sulphur-crested-cockatoo/

www.davidtaylor.com.au/birds/2021/1/17/sulphur-crested-cockatoo