By Dr Athena Qianying Lim, BSc, BVMS (Murdoch)

Gastrointestinal (GI) disease comprises a complex of clinical signs and pathological disorders affecting the digestive tract of a rabbit. Some of these disorders include GI hypomotility, dysbiosis, neoplasia, viral and parasitic, liver lobe torsion and aflatoxicosis. The common risk factors of GI disorders are a low-fibre diet, high carbohydrate or fat diet, stressful events, underlying disease, pain, decreased water intake and medications such as prolonged use of antibiotics causing dysbiosis.

Gastrointestinal (GI) ileus or stasis is a syndrome of reduced or absent GI motility, a common issue in companion pet rabbits. Rabbits are usually presented with hyporexia or anorexia, reduced or absent faecal output, lethargy and exhibit painful behaviours (teeth grinding, hunched position, isolated or less social, digging or scratching) and collapse can be seen in severe cases due to hypovolemic shock. GI ileus can be further categorized into non-obstructive and obstructive ileus, in which clinical signs can appear similar. Hairball/trichobezoar are common cause responsible for most of the obstructive cases but other causes include adhesions, strictures, impacted dry ingesta, intussusception, neoplasia, foreign body and extraluminal compression (latter are rare) are reported too.

Abdominal palpation during physical examination is crucial in differentiating if ileus is suggestive of an obstruction such as gastric size, gastric content and if gas is present.

Diagnostics

Initial diagnostics tests including blood work (complete blood count/PCV with TP, blood glucose biochemistry) and radiographs are recommended.

Abdominal radiographs can assist in categorising GI hypomotility disorders into non-obstructive versus obstructive ileus (bloat/tympany).

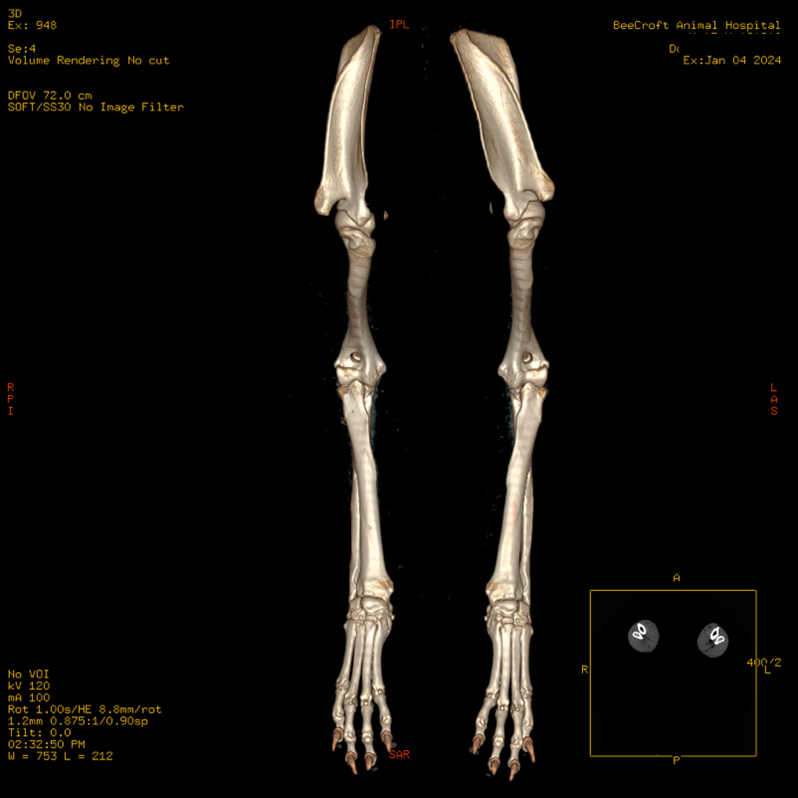

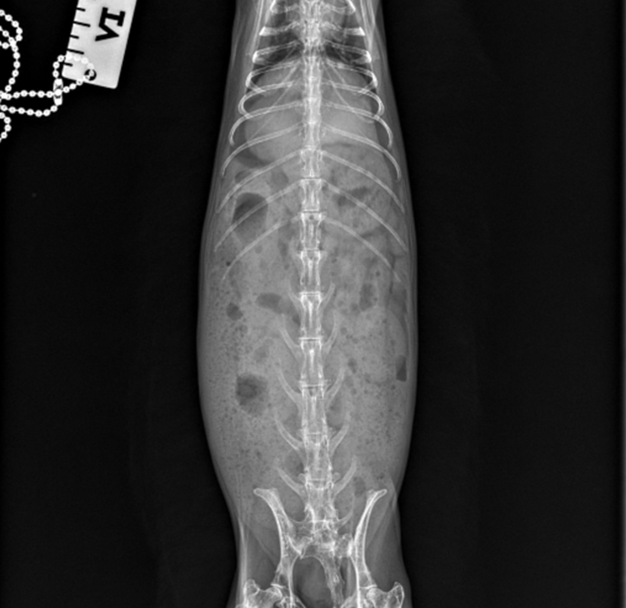

In a healthy rabbit, the gastric content on the radiograph usually has a heterogenous soft tissue opacity with a distribution of fine gas pockets. A small layer of gas around the ingesta might be seen as well (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1. Healthy rabbit abdominal radiograph lateral view.

Figure 2. Healthy rabbit abdominal radiograph ventrolateral view.

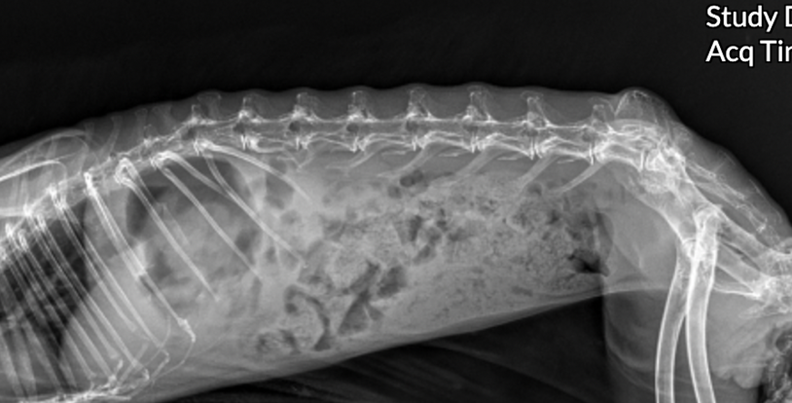

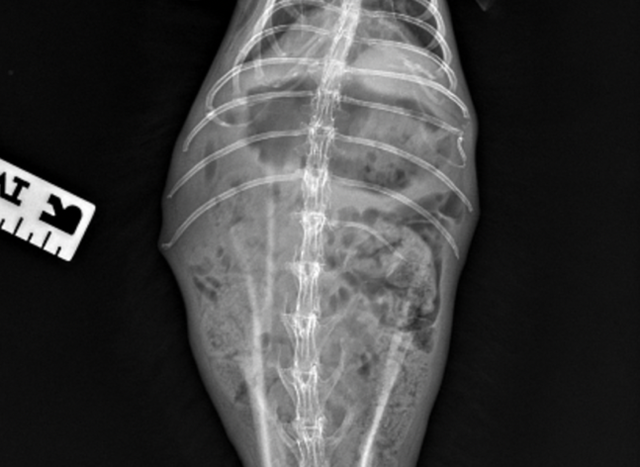

In non-obstructive ileus, a moderate to marked distended ingesta-filled stomach is present. There may be signs of a small bowel dilation and/or gas pocket/cap in the gastric fundus (Figures 3 & 4). Cecal tympany or impaction may also be diagnosed on radiographs.

Figure 3. Rabbit with GI stasis abdominal radiograph lateral view. Gas pocket/cap seen in gastric fundus.

Figure 4. Rabbit with GI stasis abdominal radiograph ventrolateral. View. Gas pocket/cap seen in gastric fundus.

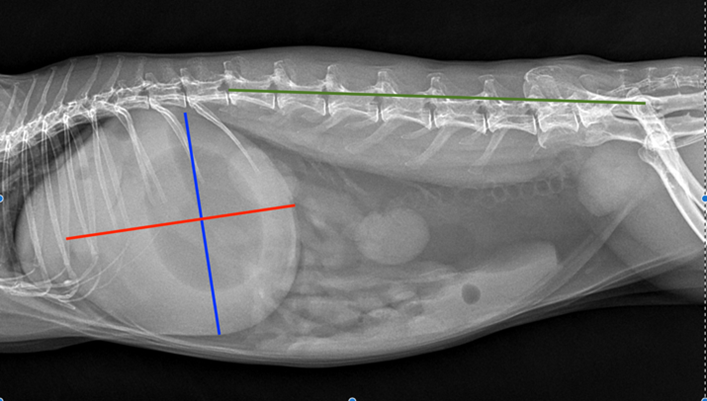

In cases of GI obstruction, severe enlargement of the gastric and intestinal dilation is seen. The gastric is filled with fluid and may have a prominent gas cap/pocket which gives a “fried-egg” appearance. Measurements of the gastric axis may be performed to assist in differentiating ileus from obstructive cases. In cases of intestinal obstruction, the summed length and width of the stomach are greater or equal to the length of the 1st lumbar vertebrae to the coxofemoral joint.

The gastric length and height were measured at 90° angles to each other, with length parallel to the 13th thoracic vertebra and height perpendicular (Figure 3.) Another criteria that is suggestive of intestinal obstruction is where the caudal aspect of the gastric wall extends beyond the 2nd lumbar vertebrae 2.

Figure 5 (left) & 6 (right). Comparison of bloated rabbit versus healthy rabbit. Summed length of gastric length (blue line) and width (red line) at 90° perpendicular to each other, is greater or equal to length between the cranial aspect of 1st lumbar vertebrae (L1) and coxofemoral joint (green line) in bloated rabbit. Source Denbenham et al., 2019

Complete blood count and biochemistry profile in a GI stasis rabbit are generally unremarkable other than an indication of dehydration. On the other hand, azotemia and sometimes renal failure can be seen in acute obstruction. Blood glucose (BG) can be useful as a prognostic indicator and determining if highly suggestive of obstruction, a recent study shows the comparison of a mean BG of 444.6mg/dl or 24.7mmol/l in rabbits with confirmed intestinal obstruction with a mean BG of 153mg/dl or 8.5mmol/l in rabbits diagnosed with GI stasis. Severe hyperglycemia of >360mg/dl or >20mmol/l in conjunction with severe hyponatremia of <129 mEq/l carries a poor prognosis.

It is paramount to check liver enzymes on the biochemistry profile and recommend additional imaging such as abdominal ultrasound if necessary to rule out liver torsion. This disease is overrepresented in lop-eared rabbits which is a common breed in Singapore.

Treatment

The fundamental approach in treating GI disorder includes rehydration, pain relief and supportive care. Depending on the hydration status of the patient, fluid therapy may vary from subcutaneous fluids to intravenous fluids. Pain relief includes the use of opioids such as buprenorphine or methadone and/or the use of maropitant citrate to help with visceral pain. Other analgesia options also include lidocaine continuous rate infusion (CRI). The grimace pain scale which assesses facial pain in rabbits can be beneficial in determining if a multi-modal analgesia approach is required.

The use of intestinal prokinetics such as metoclopramide and cisapride can be beneficial. In the initial stages in dehydrated patients with moderate to severe ileus, parental administration is preferred, followed by oral route administration.

Other treatments such as the use of lubricants (e.g., petroleum laxatives, mineral oil, hairball paste) may aid with ileus. It is however important to monitor stool consistency as soft stools or diarrhoea may be observed.

In cases of severe GI hypomotility, hypovolemic shock can develop quickly. Fluid resuscitation can be done effectively by intravenous (IV) route. Initial shock fluid bolus can be given using isotonic crystalloid fluids and/or colloids e.g., hypertonic saline or hetastarch. Aggressive fluid therapy at 2-3 times maintenance rate is often required, and the patient should always be reassessed for signs of fluid overloading during fluid therapy.

Decompression of the gastric using an orogastric or nasogastric tube should be attempted to reduce gastric size if extreme gastric tympany with water or gas is present. Sedation and/or general anaesthesia is required. Prognosis is grave when fluid collected is odorous, dark brown or black as this highly indicate stomach necrosis. One should take note never to perform percutaneous trocharization of the stomach due to the risk of stomach rupture and, hence causing peritonitis.

A study in rabbits with gastric bloat indicated 89% of the cases were treated successfully with medical treatment with a mean treatment course of 3 days hence making medical treatment favorable7. However surgical intervention may be warranted if gastric decompression is unsuccessful.

Antibiotics such as metronidazole or penicillin G can be used in cases of dysbiosis, especially in Clostridium species overgrowth, leading to development of enterotoxaemia.

Other forms of supportive care such as assisted feeding with critical care should be offered to anorexic or hyporexic patients to assist with peristaltic movements and to prevent development of hepatic lipidosis. However, if severe gastric dilation is present, it is important to reduce feeding volume/frequency and reassess the patient for obstruction.

The treatment for GI stasis should be continued until the patient is no longer anorexic and passes stools. Pets should be offered a normal diet of hay, vegetables and restricted amount of pellets during the convalescent period.

Reference

- Bonvehi, C., Ardiaca M., Barrera S., Cuesta M., & Montesinos A. (2014) Prevalence and types of hyponatremia, its relationship with hyperglycemia and mortality in ill pet rabbits. Veterinary Record. doi: 10.1136/vr.102054

- Debenham, J.J., Brinchmann, T., Sheen, J., & Vella, D (2019). Radiographic diagnosis of small intestinal obstruction in pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): 63 cases. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 60(11), 691-696.

- Harcourt-Brown, F.M. & Harcourt-Brown, S.F. (2012). Clinical value of blood glucose measurement in pet rabbits. Veterinary Record 170(26): 674

- Ozawa, SM., Hawkins, M.G., Drazenovich, T. L., Kass, P. H., & Knych, H.k. (2019). Pharmacokinetics of maropitant citrate in New Zealand White rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). American Journal of Veterinary Research, 80(10), 963-968.

- Proença, L., Pardo, M., & Sadar., M. (2022). Liver & Gut Emergencies. Emergency Care for Zoomed (Exotic) Pets: From Crisis to Success. Vetahead. https://www.vetahead.vet/

- Quesenberry K., Orcutt C.J., Mans, C., Carpenter J. W., Oglesbee, B. & Lord, B. (2021) Gastrointestinal Diseases of Rabbits. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents Clinical medicine & Surgery. Elsevier, Inc. Missouri

- Schuhmann, B., & Cope, I., (2014). Medical treatment of 145 cases of gastric dilatation in rabbits. Veterinary Record. doi: 10.1136/vr.102491.

- Schnellbacher, R.W., Divers., S.J., Comolli, J.R., Beaufrere, H., Maglarass, C.H., Andrade, N., …. $ Mayer, J. (2017). Effects of intravenous administration of lidocaine and buprenorphine on gastrointestinal tract motility and signs of pain in New Zealand White rabbits after ovariohysterectomy. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 78(12): 1359-1371.