By Dr Ce Xi Foo, BVetMed(RVC)

IVDD is a spinal cord condition involving disc degeneration resulting in disc herniation. Compression of the spinal cord can result in pain and/or neurological deficits.

IVDD can be classified into 3 different types:

- Hansen type I: Chondroid degeneration with calcification of the nucleus pulposus and weakening of the dorsal annulus fibrosus. This results in extrusion of the abnormal nucleus pulposus into the vertebrae canal leading to spinal cord damage. Type I is commonly seen in younger (~2-6years old) small breed dogs; especially chondrodystrophic breeds (ie. dachshund and french bulldogs). Type 1 is usually characterised by acute onset.

- Hansen type II: Fibroid degeneration with progressive thickening of the dorsal annulus fibrosus which protrudes into the vertebral canal. Type II IVDD is more common in older (5years old and older) non-chondrodystrophic, larger breed dogs. Symptoms may be chronic and the client may report slow progression of clinical signs.

- Type III: It is a low volume-high-velocity form of herniation into the vertebrae canal that is typically non-compressive. Type III extrusion is more commonly seen in older chondrodystrophic dogs but can also be seen in any dog.

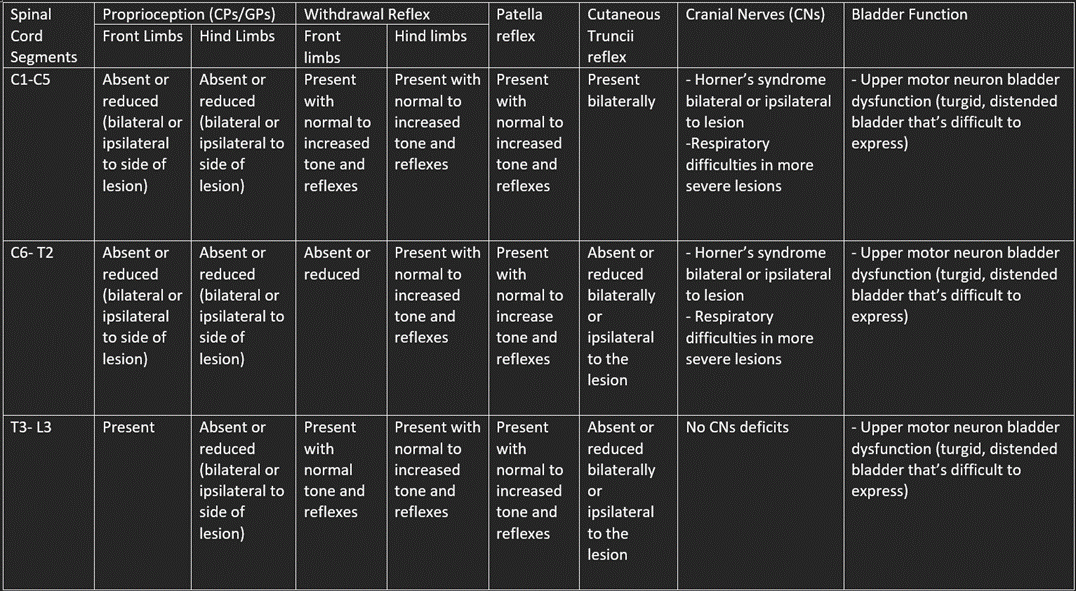

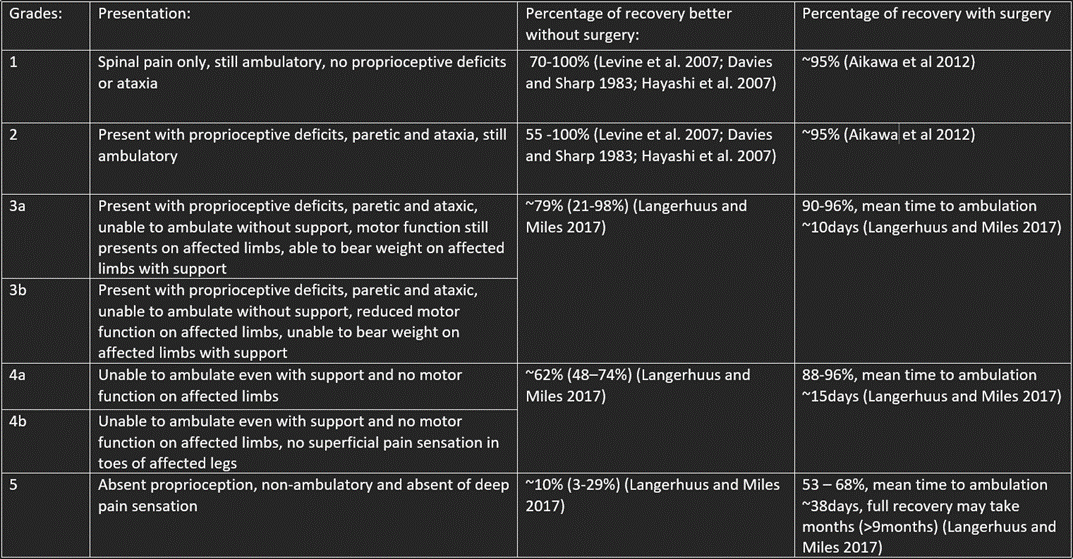

Dogs presented with IVDD will exhibit different clinical signs depending on the location of the lesion and the grade of the disease. The clinical signs can range from spinal pain for grade 1 IVDD to loss of limb function and deep pain sensation for grade 5 IVDD. Details of the clinical signs and physical examination are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Clinical signs and physical examination findings on dogs with IVDD affecting different spinal segments

Table 2. Grade 1-5 IVDD and prognosis with surgical and non-surgical management

In general, dogs presented with clinical signs of IVDD should receive workup even if the grade of neurological impairment is low. Clinical examination and history alone cannot distinguish IVDD from other causes of spinal pathology. Computerized tomography with or without myelogram or magnetic resonance imaging can help confirm a diagnosis and, if indicated, aid in surgical planning. The decision to take a patient to surgery is not based on the extent of compression alone and will typically involve the severity of neurological impairment or pain, clinical history and other general patient considerations. Although a recent review paper by Natasha J. Olby et al. (2020) did no show that duration from onset of non-ambulatory status to surgical decompression affects overall outcome of recovery, earlier surgical intervention was shown to speed up recovery duration. Hence, it is still advisable to get dogs with suspected spinal disease to be investigated as soon as possible.

Figure 1. shows a sagittal view of a CT image of the thoracolumbar spine after myelogram. The red arrows indicate radiopaque contrast passing thru the subarachnoid space and the circled region shows the area of disc extrusion where there is a lack of contrast in the subarachnoid space at that region.

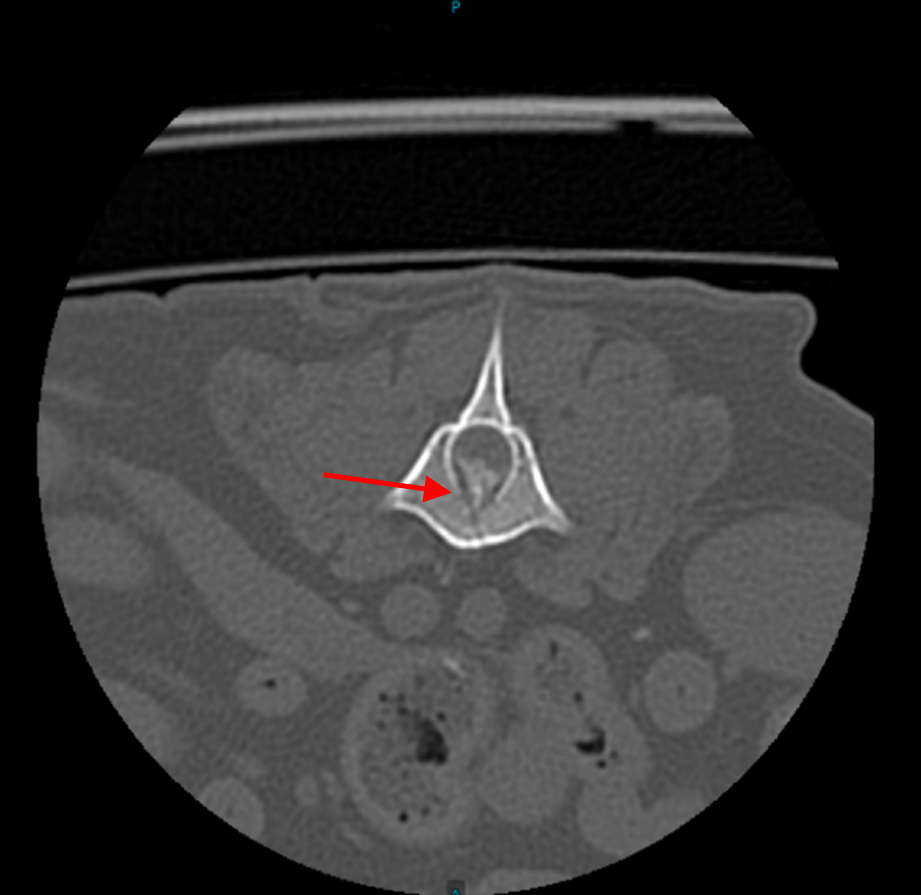

Figure 2. shows a transverse view of a CT image of the thoracolumbar spine after myelogram. The red arrow indicates the calcified disc material extruding into the spinal canal and causing compression of the spinal cord.

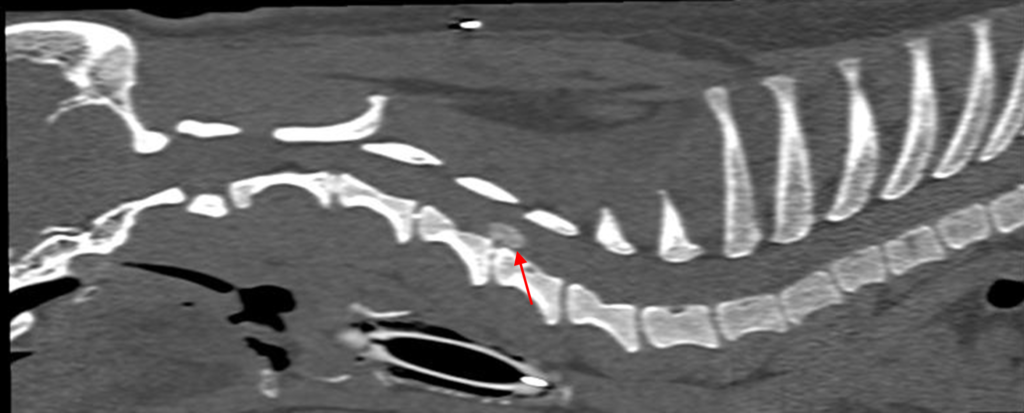

Figure 3. shows a sagittal view of a CT image of the cervical spine without contrast. The red arrows indicate the area of calcified disc material extruding into the spinal canal.

Figure 4. shows a transverse view of a CT image of the cervical spine without contrast. The red arrows indicate the area of calcified disc material extruding into the spinal canal.

References

- Aikawa et al, Long-term neurologic outcome of hemilaminectomy and disk fenestration for treatment of dogs with thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation: 831 cases [2000 -2007], Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2012, 241; 1617-1626

- Davis J. V. and Sharp N. J. H., A comparison of conservative treatment and fenestration for thoracolumbar intervertebral disc disease in the dog, Journal of Small Animal Practice, 1983, 24; 721-729

- Hayashi A. M. et al, Evaluation of electroacupuncture treatment for thoracolumbar intervertebral disk disease in dogs, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2007, 231; 913-918

- Levine J. M. et al, Evaluation of the success of medical management for presumptive thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation in dogs, Veterinary Surgery, 2007, 36; 482-491

- Langerhuus L and Miles J., Proportion recovery and times to ambulation for non-ambulatory dogs with thoracolumbar disc extrusions treated with hemilaminectomy or conservative treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-series studies, Veterinary Journal, 2017, 220; 7-16

- Natasha J. Olby et al, Prognostic factors in canine acute intervertebral disc disease, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2020, Volume 7

- Curtis W. Dewey and Ronaldo C. da Costa, Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology 3rd Edition: Chapter 13- Myelopathies: Disorders of the Spinal Cord, 2016

- Simon Platt and Natasha J. Olby, BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology Fourth Edition: Chapter 14 to 17, 2014