Soft tissue mobilisation (STM), or massage, is a form of manual therapy in animal rehabilitation which involves hands-on techniques performed to treat a variety of conditions, including musculoskeletal injuries, post-surgical pain, and chronic pain (Goff and Jull, 2007). It is a systemic application of varying intensity of manual pressure and mobilisation to the skin, soft tissues, tendon, ligaments, fascia and muscle. STM aims to aid in pain relief and management, as well as improve joint motion and overall function (Brunk et al., 2021).

Therapeutic effects of STM

- Reduces pain

- Improves range of motion (ROM)

- Increase blood circulation

- Improves lymphatic drainage

- Enhances tissue healing

- Relaxes muscles

- Reduces stress and anxiety

Indications of STM (Millis and Levine, 2014)

Patients recovering post-surgery will also benefit greatly from STM to preserve muscle tone and condition. STM aids in the recovery process by promoting blood circulation and reduces the formation of scar tissue. It helps maintain flexibility and mobility in the joints and soft tissues to prevent further loss of function and muscle atrophy, particularly when cage rest or restricted exercise is necessary for recovery.

Musculoskeletal conditions that may benefit from STM include some of the following:

- Arthritis

- Joint Dysfunction

- Muscular strains (e.g., iliopsoas strain)

- Back pain

- Hip Dysplasia

- Elbow Dysplasia

- Patella luxation

- Cranial Cruciate Ligament Ruptures

- Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD)

*Note: STM can help manage these conditions but will not resolve the underlying cause.

Contraindications of STM

Conditions that are not suitable for manual therapy includes some of the following (Robinson, 2022):

- Acute inflammation

- Infectious diseases including skin conditions (e.g., ringworm)

- Open wounds or infections

- Neoplasia

- Unstable fractures or healing bones

- Severe Osteoarthritis

- Acute hematoma

Soft tissue assessment

To determine whether STM is suitable for a patient, a thorough evaluation can first be performed to allow identification of any swelling, discomfort, pain and/or inflammation of the soft tissues. Ensure that the patient is on an even surface with adequate lighting. The patient should also be observed from a cranial, caudal, dorsal, and lateral viewpoint.

Static Assessment

Static assessment is important to identify lameness in the limbs, and the presence of abnormalities and compensations. When the patient is in a neutral standing position, observe the patient’s posture and note for any relevant abnormalities or asymmetries:

From the cranial aspect:

- Mentation and position of head (including head tilt/turn).

- Limb weight bearing and distribution (e.g., neutral, pronation/supination, abduction/adduction, varus/valgus, lateral/medial placement).

- Trunk symmetry.

- Obvious swelling or soreness of the head, body, and limbs.

From the caudal aspect:

- Pelvic and trunk symmetry.

- Height of pelvic bony landmarks.

- Limb weight bearing and distribution.

- Obvious swelling or soreness of the head, body, and limbs.

From the dorsal aspect:

- Spinal curvatures (e.g., kyphotic, lordotic).

- Pelvic and trunk symmetry.

- Alignment of pelvic bony landmarks.

From the lateral aspect:

- Spinal curvatures (e.g., kyphotic, lordotic).

- Limb weight-bearing and distribution (e.g., neutral, varus/valgus, lateral/medial placement, cranial/caudal

- weight-shifting).

- Obvious swelling or soreness

- of the head, body, and limbs.

- Angle of scapula, spinal curves/posture.

- Head and pelvic position and carriage.

- Coverage of muscle/other soft tissue (e.g., muscle atrophy).

Gait Assessment

The patient should be instructed to walk in a straight line, trot in a straight line, and perform clockwise and anticlockwise turns. Observe the patient’s gait and movement to identify the presence of abnormalities and compensations. Note the symmetry of the body, ease of limb movement (e.g., limping, head nodding, swing/stance phase of a limb, pronation/supination, abduction/adduction, dragging, buckling, knuckling, ataxia) and spinal posture (e.g., kyphotic/lordotic spinal posture, side flexion).

Palpation (spine, forelimbs, hindlimbs)

After gait observation, palpation is performed to assess the patient’s musculoskeletal structure and muscle tone. Begin by palpating the paraspinal muscles along the patient’s spine, starting from the wings of the atlas, working down to the vertebral bodies of C2-6, thoracic spine, ribs, sternum, lumbosacral junction, wings of the ilium, sacral spine, and the tail. Note for the presence of any skeletal abnormalities, asymmetry, wounds, and lumps. Muscle fasciculations or tension along the spine might indicate soreness and discomfort.

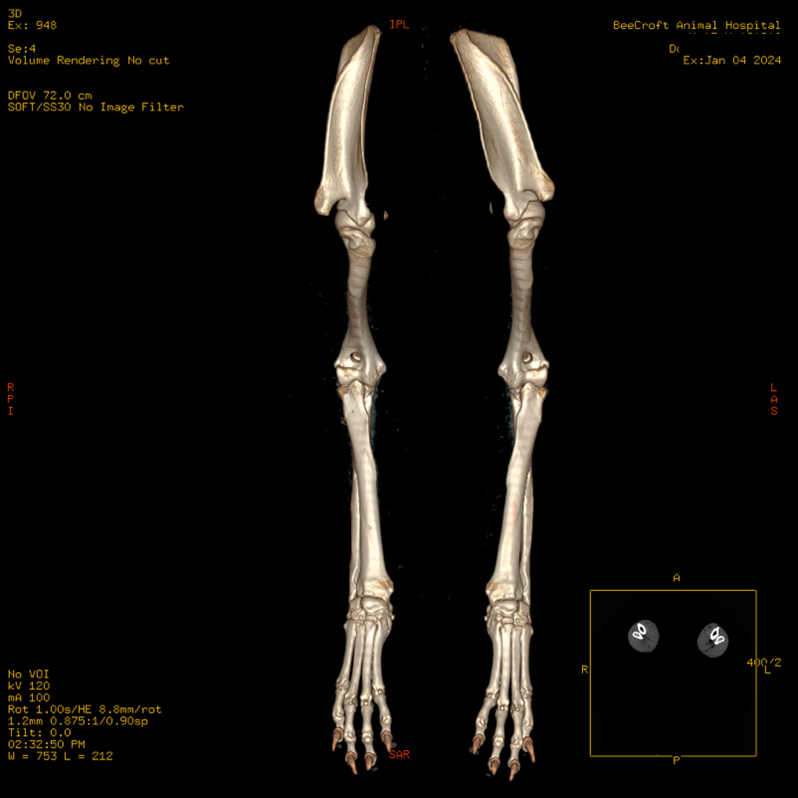

Palpation down the forelimbs can be assessed one limb at a time, or bilaterally to recognise any asymmetry of position and surrounding musculature. Take note of bony landmarks, limb ROM, and joint stability during palpation. Assessment is preferably done with the patient in lateral recumbency to allow a relaxed and neutral position of the limb. However, this can also be performed when the patient is in a neutral standing position.

Start from the dorsal border of the scapula, working distally to the metacarpals of each limb. Palpate the trapezius, deltoids, biceps, triceps, latissimus dorsi, carpal flexors and extensors, and note for any discomfort or increased muscle tone when assessed.

Similarly, palpation down the hindlimbs can be assessed one limb at a time, or bilaterally to recognise any asymmetry of position and surrounding musculature. Begin from the greater trochanter, working distally to the metatarsals or each limb. Palpate the quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteals, sartorius, pectineus, iliopsoas, gastrocnemius, cranial tibial, and digital flexors, and extensors to identify signs of muscle atrophy or fasciculations.

The ROM of all four limbs should also be assessed and this is best evaluated when the patient is in lateral recumbency. The quality of movement and end feel should also be identified when evaluating ROM of the forelimbs, starting from the metacarpus, moving proximally to the carpus, elbows, and shoulders. Assessment of the hindlimbs should also start from the metatarsus, moving proximally to the hocks, stifles, then hips. Resistance and restriction to achieve ROM and end feels should be specified if significant.

Massage Techniques ((Lindley and Watson, 2010; Millis and Levine, 2014; Zink and Van Dyke, 2013)

Massage comprises numerous techniques which involve a series of hand motions along the body. The following techniques are applicable in all muscle groups and at any stage of recovery. The following techniques are some of the most used techniques but is not an exhaustive list.

Stroking

At the initial stage, stroking is used at the initial stage with the aim of calming and soothing the patient prior to the commencement of the massage treatment itself. This is also commonly carried out at the end of the session. This technique is especially helpful with patients who are anxious or stressed due to pain and discomfort or being in an unfamiliar environment. In addition, it is particularly useful to identify and evaluate the presence of abnormalities such as swelling, masses, temperature differences between various body areas, and muscle tension.

With the patient in a neutral standing/lying position, glide your hand gently over the animal from neck to tail, and down all four limbs. Stroking should be performed in continuous contact with the body using light pressure for approximately 30-60 seconds.

Effleurage

This is a gliding technique that is used to commence a massage and consists of long and slow strokes usually performed parallel to the muscle fibers. It is used for relaxation, to reduce swelling and edema, assist in the removal of toxins from the body via the lymphatic system, and to increase blood circulation. Movement around the body should be performed with a light to medium pressure, and towards the direction of the heart, beginning from the distal aspect of the body (ie from the paws) and moving proximally towards the lymph nodes.

Pressure Techniques

Petrissage

Petrissage refers to a massage technique which applies deeper pressure to compress and release underlying tissues and muscles. It involves short and brisk strokes parallel or perpendicular to the muscle fibers. This technique is beneficial for mobilisation of soft tissues, relieves muscle tension, muscle spasms, and knots in soft tissues, and improves circulation and lymphatic flow.

Types of petrissages includes kneading, picking-up, wringing and skin rolling:

Kneading – Muscles are pressed alternately by one or both hands, with the hand/fingers moving in a circular motion.

Picking-up – Muscles are grasped and lifted away from the body, and subsequently squeezed and released.

Wringing – Using both hands, grasp and lift the tissues. Move both hands in opposite directions to stretch the tissues for 2-5 seconds, and slowly release.

Skin rolling – Grasp the skin and subcutaneous tissue between both fingers and thumbs. Roll the tissues forwards, then backwards to release any tissue adhesions. Move along the body caudally to cranially along the spine, ventrally to dorsally along the latissimus dorsi, and distally to proximally along the limbs.

Ischemic compression

Ischemic compression is a technique which applies continuous medium to deep pressure to a localised area of hyperactivity. It intentionally blocks blood flow to a region and release of pressure to the targeted point stimulates a resurgence of blood flow. Ischemic compression helps to restore blood circulation, decreases tension in the muscles, and promotes healing. Pressure can be applied to the affected area for 30-60 seconds, followed by stretching of the muscle for 30 seconds after.

Deep transverse friction or Cross friction massage

Deep transverse friction massage is a therapeutic technique using cross-grain movements applied to the muscle, tendon, and ligaments of the affected region (Fig. 2). It is beneficial for breaking down adhesions and scar tissue, improving tissue flexibility. When pressure is applied and released on the affected area, increased blood circulation will occur, allowing for more nutrients and oxygen to be transported to the surrounding tissues. Deep transverse friction massage promotes tissue healing and reduces pain, thereby enhancing mobility and function of the muscle.

Fig. 2: Deep transverse massage

Locate the area of concern by palpating for tightness, tenderness, and/or knots. Using the fingers, apply pressure with small deep movements in a transverse direction, perpendicular to the muscle fibers and underlying soft tissues in the targeted region. Deep transverse friction may not be comfortable, hence a gentle massage and stretching can be performed after the session to promote relaxation. Deep transverse friction massage is usually performed for 30 to 60-second repetitions until desensitisation occurs. Tissues should be treated with other forms of modalities should desensitisation not take place after the stipulated amount of time.

Conclusion

Manual therapy is an important aspect of rehabilitation to identify any form of abnormalities in musculoskeletal function and posture. STM, as a form of a therapeutic technique, consists of various techniques to improve mobility, flexibility, function of soft tissues and muscles. Despite limited evidence on the effectiveness of STM on specific clinical indications, numerous articles have reviewed topics on the benefits of massage which is deemed beneficial on one’s physiological effects (Bergh et al., 2022). The application of these manual techniques to the soft tissues and muscles aims to aid in managing our patient’s pain and discomfort and can result in a positive influence on their overall quality of life.

References

- Bergh, A., Asplund, K., Lund, I., Boström, A., & Hyytiäinen, H. (2022). A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine in Sport and Companion Animals: Soft Tissue Mobilization. Animals (Basel), 12(11), 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12111440

- Brunke, M., Broadhurst, M., Oliver, K., & Levine, D. (2021). Manual Therapy in Small Animal Rehabilitation. Advances in Small Animal Care, 2, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yasa.2021.07.008

- Goff, L., & Crook, T. (2007). Physiotherapy Assessment for Animals. In Animal Physiotherapy (pp. 136–163). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470751183.ch8

- Goff, L., & Jull, G. (2007). Manual Therapy. In Animal Physiotherapy (pp. 164–176). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470751183.ch9

- Lindley, S., & Watson, P. (2010). BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Rehabilitation, Supportive and Palliative Care: Case Studies in Patient Management (pp. 90-102). BSAVA.

- Millis, D. L., & Levine, D. (2014). Therapeutic Exercise and Manual Therapy. In Canine rehabilitation and physical therapy (2nd ed., pp. 464-483). Elsevier.

- Robinson, N. G. (2022). Manual Therapy in Veterinary Patients – Management and Nutrition. MSD Veterinary Manual. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/management-and-nutrition/integrative-complementary-and-alternative-veterinary-medicine/manual-therapy-in-veterinary-patients#v3311613

- Sharp, B. (2012). Feline Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation: 1. Principles and potential. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 14(9), 622–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X12458209

- Veenman, P. (2006). Animal physiotherapy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 10(4), 317-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2006.03.004

- Zink, C. M., & Van Dyke, J. B. (2013). Canine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation (pp. 100-114). Wiley-Blackwell.